Member Variance?

Variance? Whaaaat?

This is my first post and it’s basically a test, I am trying to learn how to write math equations using Mathjax (fortunately, it’s almost the same as writing in Latex). This post will be about something I encountered when I was studying for my probability theory exam..

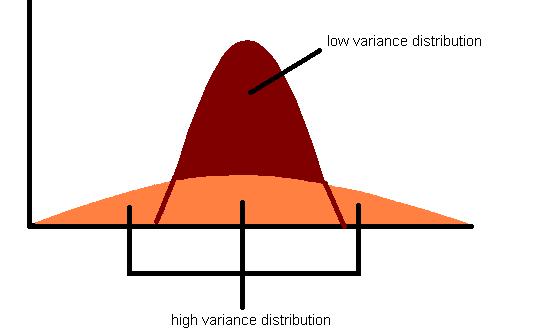

Everybody knows (hopefully) that the variance of a random variable $X$ is defined as $\mathrm{Var}[X]=\mathrm{E}[(X-\mu)^2]$, where $\mu=\mathrm{E}[X]$. So, how do we estimate in practice the variance related to some population?

A variance portrait from Raffaello

Assuming our population is represented by $X_1, X_2, …, X_n $ independent and identically distributed random variables with $\mathrm{E}[X_i]=\mu$ and $\mathrm{Var}[X_i]=\sigma^2 < + \infty$, we set $ \bar{X}_n=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i $. Then a well known estimator of variance is:

\[S_n^2 = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar{X}_n)^2 \tag{1}\label{1}\]Is it unbiased (a.k.a. does it converge to the true value)?

First, we need to recall some definitions..

Convergence in probability

A sequence $(X_n)_{n\in \mathbb{N}}$ of real-valued random variables is said to converge in probability to some other real-valued random variable $X$ , denoted $X_n \overset{P}\to X$ , if for all $\varepsilon > 0$:

\[P(|X_n −X|\geq \varepsilon) \to 0 \quad as \quad n\to \infty\](Weak) Law of Large Numbers

Since I’m lazy, you can look it up here.

Proof

Thus, showing that our estimator is unbiased is equivalent to say that $ S_n^2 \overset{P}{\to} \sigma^2 $ as $ n \to +\infty$.

To start, we can rewrite the expression for $S_n$. We observe the following:

\[\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\bar{X}_n)^2 = \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\mu)^2 - n(\bar{X}_n-\mu)^2\]Indeed:

\[\begin{align} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\bar{X}_n)^2 & = \sum_{i=1}^n ((X_i -\mu) - (\bar{X}_n - \mu))^2 = \\ & = \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\mu)^2 + \sum_{i=1}^n (\bar{X}_n -\mu)^2 - 2(\bar{X}_n - \mu)\sum_{i=1}^n(X_i - \mu) \tag{2}\label{2} \end{align}\]And we have that:

\[\sum_{i=1}^n (\bar{X}_n -\mu)^2 = n (\bar{X}_n -\mu)^2\]and:

\[\sum_{i=1}^n(X_i - \mu) = \sum_{i=1}^n X_i - n\mu = n\bar{X}_n - n\mu = n(\bar{X}_n - \mu)\]Thus in $\eqref{2}$:

\[\begin{align} & \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\mu)^2 + \sum_{i=1}^n (\bar{X}_n -\mu)^2 - 2(\bar{X}_n - \mu)\sum_{i=1}^n(X_i - \mu) = \\ & = \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\mu)^2 + n (\bar{X}_n -\mu)^2 - 2n (\bar{X}_n -\mu)^2 = \\ & = \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\mu)^2 - n (\bar{X}_n -\mu)^2 \end{align}\]as claimed.

Then in $\eqref{1}$:

\[\begin{align} S^2_n & = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar{X}_n)^2 \\ & = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\mu)^2 + \frac{n}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (\bar{X}_n -\mu)^2 \tag{3}\label{3} \end{align}\]We now consider the first term in $\eqref{3}$:

\[\frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\mu)^2 = \frac{n}{n-1}\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i -\mu)^2\]Since $ X_1, X_2, …, X_n$ are iid random variables with $\mathrm{E}[X_i]=\mu$, we can use the (weak) law of large numbers to get:

\[\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \mu)^2 \overset{P}{\to} E[(X-\mu)^2] = \mathrm{Var}[X] = \sigma^2\]Since $\frac{n}{n-1} \to 1 $ as $n \to \infty$:

\[\frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \mu)^2 = \frac{n}{n-1} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (X-i-\mu)^2 \overset{P}{\to} \sigma^2\]as $ n \to \infty $.

Now we have to show that the second term in $\eqref{3}$ converges in probability to 0. Again, since $ X_1, X_2, …, X_n$ are iid random variables with $\mathrm{E}[X_i]=\mu$, we get by the (weak) law of large numbers:

\[\bar{X}_n - \mu \overset{P}{\to} \mu-\mu = 0\]And, since $g(x)=x^2$ is a continuous function, we get that:

\[\frac{n}{n-1}(\bar{X}_n-\mu)^2 = \frac{n}{n-1}g(\bar{X}_n-\mu) \overset{P}{\to} g(0) = 0\]as $n {\to} \infty$. Thus, we have established that:

\[\frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar{X}_n)^2 \overset{P}{\to} \sigma^2\]